Rabbi Shira is a bit of a celebrity within the Jewish community and for good reason. Whenever I mention her to someone who has taken a class from her, attended a service she officiated or worked with her, the other person’s eyes light up. She’s engaging in her sermons, she’s kind to everyone she meets, but most importantly, she makes modern Judaism matter to young professionals. That’s a big deal when we’re talking about a very old faith created in the pre-Iron Age Levant and honed for centuries in non-American places.

I ran away from religion in my college years when I read the “Who Wrote the Bible” series on The Straight Dope. I felt like religion was the people in desperation or people who were looking for meaning and I wasn’t really in that category. People on their death beds cared about religion because they needed a longshot, I thought. People in poverty cared about religion because it was a way out or a ray of hope. I was (and am) a near-picture of privilege and found little to no need for the advice, philosophy and morality from Jewish scripture. I, essentially, knocked out a great part of my heritage for the sake of not wanting to associate with the Jewish community.

Right after I came back from Israel the first time, a softball teammate and friend recommended an episode of the podcast The Hidden Brain explaining the evolution of the deployment of religion. In the episode, Professor Azim Shariff explained that religion serves different purposes at different points in its lifecycle and for the lifecycle of communities. He singles out the “Old Testament God” (a phrase I don’t enjoy, largely because it frames Judaism as an archaic and vengeful faith against Christ’s more compassionate father figure. As though there isn’t a lake of fire at the end of the Christian’s books.) as a version of religion being an avenue for laws and keeping a community within an orderly system of government, versus the tribal notions of religion as a way to keep small groups together and survive. As nation-states grew, different religion changed and evolved to become different things, even to where we are now in the United States.

This really connected me with Rabbi Shira’s notion of Judaism as as a “meaning-making technology” is somewhat revolutionary. The lifecycle of America, Judaism and American Jewry is one that needs the philosophy of the various texts that Jewish people have studied for centuries, though no one certainly follows every law, nor are most of the laws interpreted the same way by every Jewish person (the old joke is “two Jews, three opinions”). There are, for example, a lot of rules on how to treat one’s slaves. These are rules that do not apply to me.

But, even those rules about ancient Judea or the Jewish Temples (the most-recent was destroyed in the first century) do have application to modernity, as do the rabbis conversing in the Talmud or the philosophy of Maimonides or Rashi.

But, a lot are some old-ass men from a different time and Rabbi Shira can bring those to the fore in a way that others do not. For a recent Shabbat sermon, she spoke of the ways that Jews can honor the holy by taking care of themselves and their community, all while tying it into an Ariana Grande concert she had recently attended with one of her kids. She – and, admittedly, she is not alone in this – tied Judaism’s historic notions of treating “strangers” well to the United States’ immigration policy. At last year’s post-Pittsburgh Solidarity Shabbat – which was so crowded that she had to do two services, back-to-back – she was able to synthesize the message of rejecting all forms of hate by tying it to scripture, all while emotionally recounting how she deals with knowing that her family is at risk for the kind of hate crimes that have hit the Jewish community recently.

I knew of her a little from going to High Holiday services and events like Solidarity Shabbat and the MLK Shabbat, but wanted to get more involved and continue to rediscover my own Judaism. I’d been on the Sixth & I email list since a 2011 Lens Lekman concert I saw there – the synagogue hosts non-Jewish concerts and book talks, as well – and, in the spring, noticed that signup was open for the Sixth & I Israel trip. Having decided I wanted to go back and wanted to be part of this trip, I applied and got accepted to be part of a trip with 31 other people to the Promised Land.

It was a magical trip. We spent time in disputed territory (The Golan Heights, the West Bank and Jerusalem) and met with Druze Israelis, Palestinian Christians and Muslims and, of course, Israeli Jews. We met with professors at Israeli universities and visited a winery up north. We traveled to a Palestinian refugee camp and toured Mt. Herzl to see the graves of those who died in the IDF. We had Kabbalat Shabbat at the Wall. We traveled to Akko and met with urban kibbutzniks. Each day, someone did a Dvar Torah (essentially, a short discussion or talk on the week’s Torah portion) to connect us to the faith. We talked a lot, in groups and one-on-one about everything from our own Jewish practices and evolution within Judaism all the way to the regular chats about life. We made plans to hang out in D.C. when we got back and we’ve largely kept those plans (we started a monthly Havdalah Club and even see one another at synagogue for many a Shabbat service). I met dozens of people I would’ve never met otherwise and really enjoyed. They are always in my heart (and my Facebook feed!).

We still hang out and I hope that continues for a lifetime. We were so close to one another for that trip and those of us still in D.C. (a few people moved away) come together every few weeks. My need for a Jewish community a reason for my participation in the trip and I am so thankful that everyone involved was such a beautiful person.

—

I think about Israel a lot. I think about it because it speaks for worldwide Jewry, for good and (more often, sadly) for ill. I think about moving there because my homeland’s ruling class is increasingly hostile to its populace and general intolerance to religious and ethnic minorities – most certainly including anti-semitism – is growing here. Israel is an apartheid state, ruled by a, let’s say, a rough and corrupt customer. But if that’s the way a lot of governments (including my own) are going, I might as well move somewhere where I won’t have to take Yom Kippur off from work.

Ultimately, I don’t think it is something I can do. I am trying to learn Hebrew, but it’s really fucking hard. As European and western as Israel is, it is still a Middle Eastern nation, complete with extreme bluntness, a flexible view of time and constant strife. For all intents and purposes, it is a nation constantly at war in its own backyard and with its neighbors. Its government is awful to the people it rules via said apartheid government in the Palestinian Territories.

The Americans who move there seem to do so because of a type of faith or because of a type of belonging. Israel is, depending on who you ask, a refuge for world Jewry (this is a prevailing non-ultra religious view) or a step toward fulfillment of biblical prophesy. As mentioned above, there are a million different views of the narrative, but a huge (if not the strongest) one is that the Jewish people will occupy eretz yisrael (ארץ ישראל) – the Land of Israel, which is way more than the current nation-state’s borders – but mostly, the Jewish people will occupy Jerusalem and rebuild the holy temple, which will bring the messianic period (evangelical Christians have a version of this that suggests the third temple will bring about Jesus’ second coming).

(This is the short version of it. Wikipedia has a good rundown on rebuilding the temple here that explains it better than I can.)

I have friends who moved to Israel and I’ve done the cursory research on how to do it; the Right of Return makes it comparatively easy to move to Israel for a Jewish person like myself. All I need is some paperwork, really, including a letter confirming that I am, indeed, Jewish.

—

Of all the things on which Judaism loses me, the one I hate the most is the faith’s most stringent readings suggests that dogs are “impure” animals. Maimonides wrote it. Another sage wrote that keeping dogs for companionship is “precisely the behavior of the uncircumcised.” Recently, an Israeli city basically banned dogs. There is a notion that dogs are OK for guarding properly, but they are tools like a plough horse or a cat hunting rats.

I lost my dog recently to cancer and I, through experience, have no interest in the “impure” argument. Dogs are the greatest creatures in the world. They are, in a way, too pure for this world. But, Judaism falters in the way that the faith treats dogs. As with all ancient faiths, the evolution of said faith is the culprit; so many of the laws in Leviticus concern things that ancient desert dwellers and early agriculture types need (slaves, fields, etc.) and need the later sages to interpret.

One (somewhat) well-known Jewish tradition is the Mourner’s Kaddish. It’s a prayer said by those in mourning during the periods immediately after a death, during the prescribed period of mourning and the yahrzeit days. It’s said a lot.

But it’s for people. I looked up and down for a recent rabbinical dicta that suggested it was OK to use the kaddish as a balm for the mourning of my pet and came up empty. I’m not upset at this fact because the kaddish text speaks to the notions of the person glorifying the almighty (dogs don’t do that) and the age-old Jewish notion that dogs are impure.

—

I’ve moved away from absolutism in my life. Polemic is necessary and I do feel certain things are unmovable (which I will not get into here because I’m a journalist and have to abide conflict of interest rules). I believe in science and I believe in the reality of the corporeal world. So, I’m not attracted to following every rule within Judaism to the letter (hence, dogs, but also kashrut and shomer shabbos and the like).

And yet…

When I was in Israel and I saw the various levels of haredim, there is a latent thought in my head that sounds something like “those people are doing it right.” It comes up when I saw the ultra-orthodox men with their hats and their long bears. It comes up when I read something from Chabad (a Jewish religious group that most certainly is not mainstream, but is sorta evangelical in the small E sense). It came up when I was watching Shtisel back here in the States. And, mostly, it comes up when I think about moving there.

I don’t know if it’s an authority thing for me; I know I grew up in (and currently am a part of) a progressive community with woman rabbis and more forward-thinking views of how to apply to Judaism to modern American life. Rabbi Shira is the grand example; she hardly expects those in her congregation to live the same way a bunch of desert-dwellers in 1st-century Judea (or in 17th century Europe or whatever). She doesn’t say the same Birkhot HaShahar that I do because thanking the almighty for not being a woman is hardly applicable for anyone with an equality-minded philosophy. I probably shouldn’t say it.

But that’s the thing: The purpose of so many of these rituals is not because I believe in them or even think the words I am saying (mostly in Hebrew) are ones whose literal meaning I care about. The Birkhot HaShahar starts with a prayer that, according to one translation, thanks the almighty because he “gave the rooster intelligence to distinguish between day and night.” That is likely a European notion of the morning, but it’s not my life nonetheless (I use an iPhone alarm). The Birkhot HaShahar’s final two blessings

I was having a conversation about religion with a friend recently and noted my own reconnection with Judaism. I like community and I like ritual – even in the least-religious points in my life, I still kept Passover because I would tell people that “man needs tradition.” I still believe in this need for tradition and I like doing it because it grounds me, both in the way I interpret the words (being thankful for the things I have or caring about the modern message of ancient scripture in asking for community).

Despite his disdain for dogs as pets, I’ve been reading Maimonides a lot in the last year. Rabbi Shira mentioned him at a Shabbat sermon I attended at Nats Park in May (no, really) and tied it to Ariana Grande and finding fulfillment in community or in solitude (no, really). And that only strengthened my admiration for my rabbi. But the piece of Maimonides’ writing that hit me the strongest remains the passage in Jewish Currents put it:

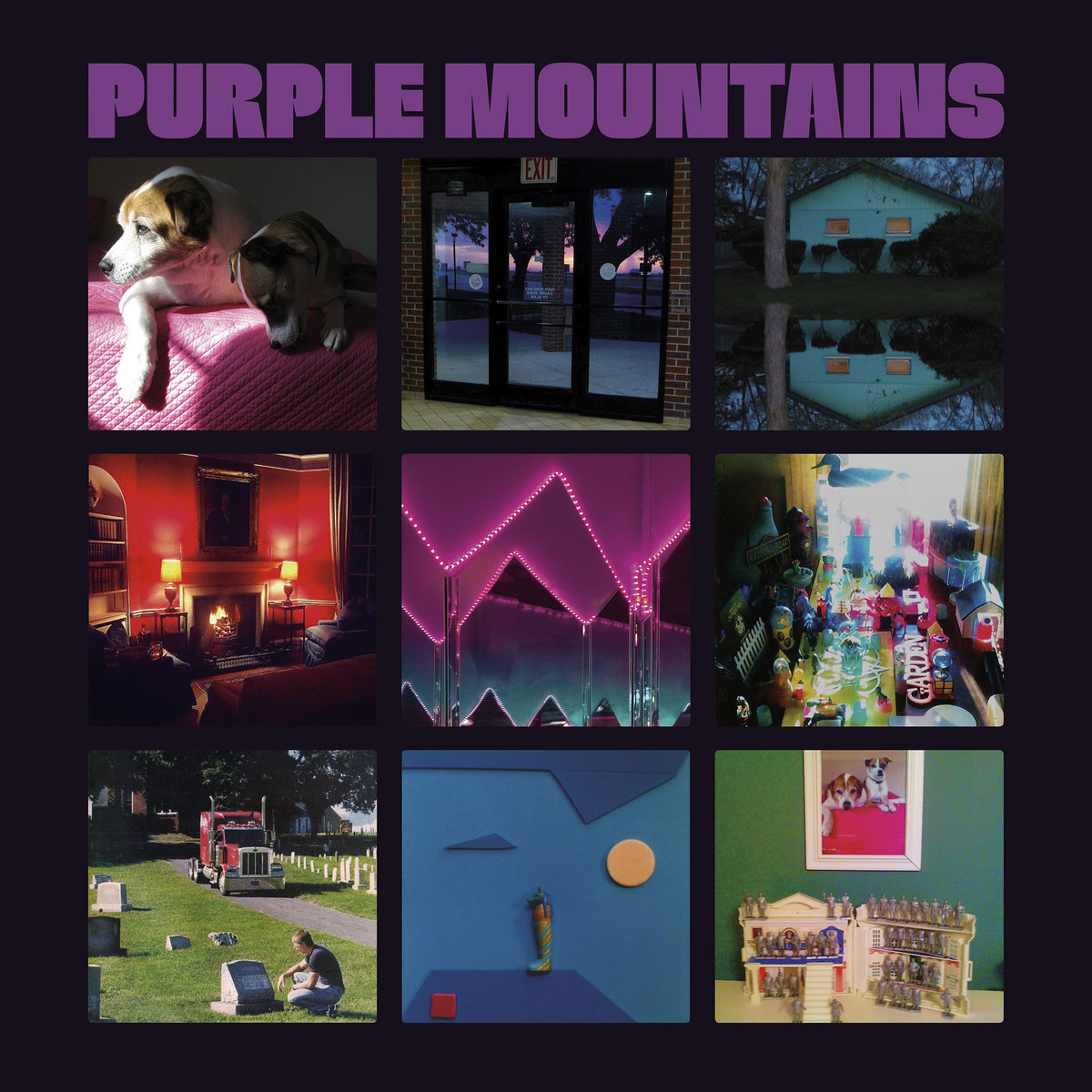

His albums took up the grand project of Jewishness, to which he came honestly: wrestling with God, playing the stranger. Watching the world die of old age while awaiting the messiah; catching the dazzling light reflected off the shattered glass of our material world.

Berman’s final album, released earlier this year after 10 years away from music, is a recitation of these themes. He examines the Jewish notions of waiting for the messianic age in “The Wild Kindness” by intoning “Instead of time there will be lateness / And let forever be delayed,” while the melancholic “Nights That Won’t Happen” references the guests at the prophets’ tents (and an old Turkish proverb). “Snow is Falling in Manhattan” similarly references the commandments to honor guests by singing “Is the ghost the host has left behind/To greet and sweep the guest inside,” using the song as a home metaphor.

far better people than I – struggle with an unmoving almighty. “Margaritas at the Mall” has a title that seems easily thrown in, but the first verse hits like a ton of bricks with Berman describing existence as “A place I wake up blushing like I’m ashamed to be alive.” The song moves to its most inquisitive with the pre-chorus lyrics:

How long can a world go on under such a subtle God?

How long can a world go on with no new word from God?

See the plod of the flawed individual looking for a nod from God

Trodding the sod of the visible with no new word from God

Berman’s sentiment is not a new one, either from him or from the world at-large. It’s the thing under which we’ve all struggled when dealing with some concept of universal justice or a just deity or whatever. Berman’s mastery of it is what makes him so eloquent, but it’s a thing we all deal with whenever we examine our faith/spirituality/etc.

Berman sets it out perfectly. How does the world turn with so much injustice? How does existence continue when justice is so far away? They are decidedly spiritual questions that Jewish people have been asking for centuries.

I don’t know where this will all lead, regarding my own relationship with Judaism. I don’t see myself ending up Haredi and growing out my payos. I also don’t see myself abandoning my trip buddies or my synagogue anytime soon. But, I will look again when saying the morning blesses, because that sexist nonsense (however traditional it is) doesn’t work for me.